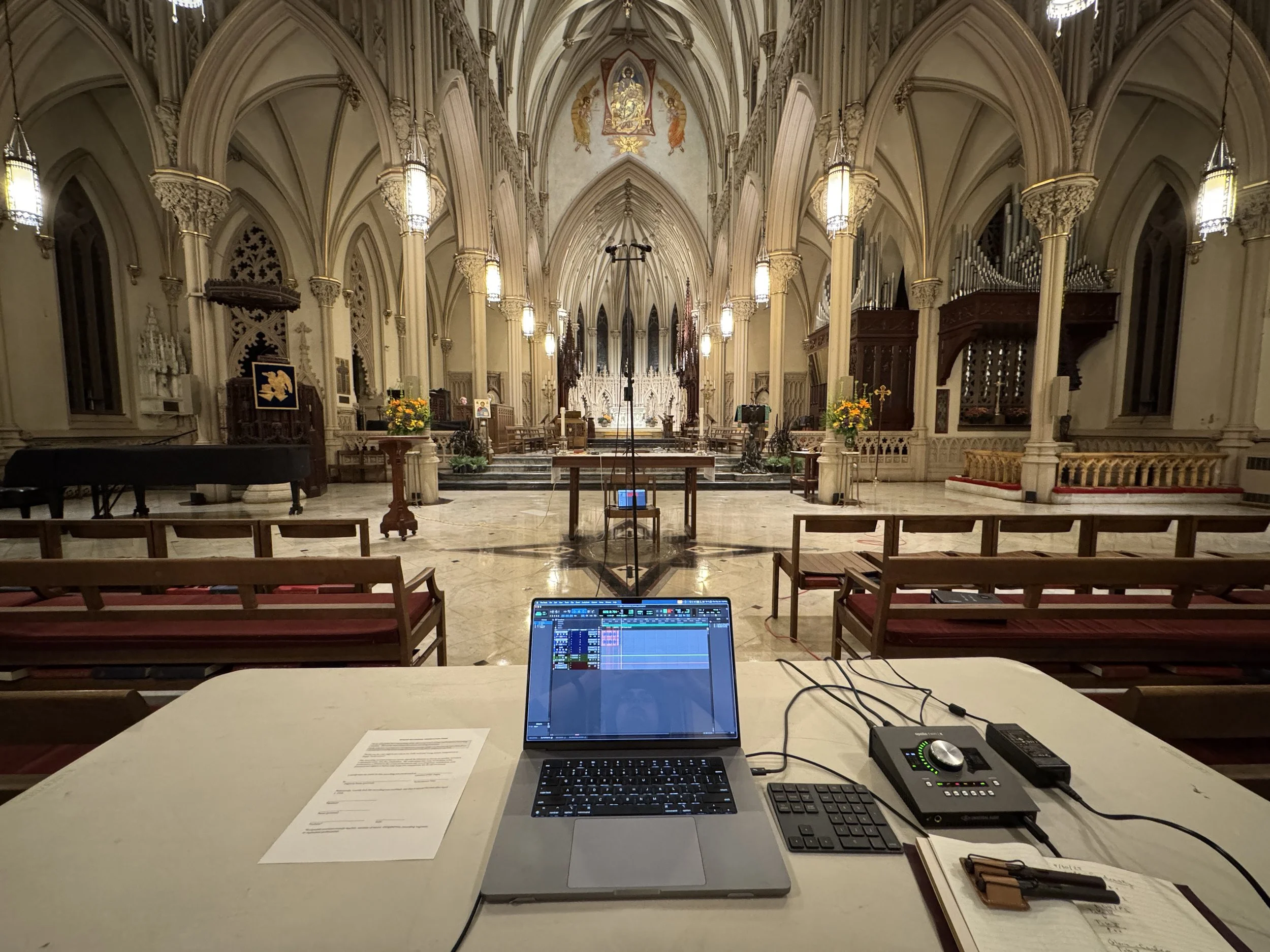

Margaret Vardell Sandresky, L’homme armé Organ Mass (2025)

Audio Engineer

One of the most unique aspects of ambisonics recording techniques is versatility. In immersive/spatial productions, ambisonics’s role is relatively obvious and very effective. In traditional stereo productions, however, ambisonics microphones can positively trounce standard microphones in terms of adaptability. But why is this, and how does this highlight the fundamental difference in the expected listener experience between these two production paradigms?

The nature of immersive productions force the creator to relinquish a certain amount of control. They don’t know how, exactly, a listener will choose to experience the content. Will they sit in one place, staring straight ahead? Or, will they stand up, walk around, tilt their head, face different directions, or all four at once? Stereo productions do not force this particular concession. At any moment, the creator can definitively choose what the listener will hear, and (largely) how they will hear it; there’s not the same risk the experience be drastically altered mid-way through the content.

At its core, ambisonics depicts gradients of sound pressure from (at least) four physical directions related to a single point in space, often captured with four very close microphone capsules facing outwards from opposing vertices of a cube. Since the varying magnitudinal pressure (i.e. gradient) from each capsule is inherently associated with the direction its facing, a steerable sphere of sound is created when these capsules are joined together.

In immersive formats, this sound is usually steered as the listener moves their head. This makes for great sound fields and ambience. However, in stereo, ambisonics grants virtually unprecedented control over the production’s aesthetic during post. Didn’t capture the snare just right? No problem, you now have more options. Too much trumpet in the brass section? Just steer it slightly closer to the trombones. Want to record group backing vocals all at once but maintain a direct signal from each voice? Record once, duplicate the tracks, and steer each one to face each vocalist. Truly, the utility on display is virtually unparalleled. So, why aren’t we all using them all the time?

For one, there’s the price to performance ratio. First order ambisonics (FOA) microphones are often $1k and up, and that cost is split between 4 capsules. As a result, those capsules are often (though not always) inferior to those on a standard, single-capsule microphone at the same price. There’s also the fidelity: FOA is subject to spatial image smearing, loss of critical high frequency energy, and poor localization performance, all of which may be mitigated by higher order ambisonics capture. However, higher order ambisonics capture requires a higher order ambisonics microphone with more capsules at a continually increasing cost, which leads back to the initial problem. Further, regardless of the ambisonics order used, decoding this content into something usable is not a universal process, and poor decoding frequently leads to unintended auditory artifacts.

There are no silver bullets here, simply more tools for the belt. There is no replacement for attention to detail and careful forethought. An ambisonic microphone alone will never capture the paradoxically simultaneous detail and breadth of a well placed Decca tree over an orchestra, nor the quiet intimacy of two TLM 103s on a soft singer and her acoustic guitar’s twelfth fret. Of course, that doesn’t mean ambisonics doesn’t deserve a spot in the repertoire - it just means it’s important to understand that repertoire.

Provided here is a stereo recording of Gloria from Margaret Vardell Sandresky’s L’homme armé Organ Mass, recorded with a first-order ambisonics microphone and an NOS stereo pair, performed by David Preston.

Spatial Organ Recordings (2024 - Ongoing)

Audio Engineer, Lead Investigator, Lead Author

Within stereo classical music recording, specialized techniques for the organ have largely been relegated to footnotes or appendices in the face of more accessible instruments and ensembles. As immersive recording techniques for classical music continue to develop, little convention has been established regarding immersive organ recording techniques. Furthermore, a significant portion of the organ repertoire does not exist in any sound recorded form at all, and risks being lost or forgotten over time. Pipe organs already face numerous threats to their existence, including decreased attendance to houses of worship, under-funding, improper restoration, and electronic substitutes.

While the organ repertoire is vast, experiencing that repertoire in a form similar to that intended by the composer is often inconvenient, as stereo recordings frequently don’t provide a deep level of psychoacoustic immersion, and in-person experiences are realistically limited to those located within a convenient distance of a house of worship with a skilled organist willing to learn and perform said repertoire.

This project aims to open the door for expanded conversation around establishing best practices and techniques for recording and reproducing pipe organ music in an effort to both preserve the unique medium and broaden its appeal and accessibility to a wider audience through an immersive environment.

This publication (presented at the 157th Audio Engineering Society Convention) may be found here. An ambisonics & accompanying 360º video recording of Schumann’s Prelude & Fugue in D minor Op. 16, No. 3 is provided on this page.

Please be aware that spatial audio in 360º YouTube videos is only functional as an embedded video, so please click the play button on this page for the full experience.

Height Layer Comparison (2024)

Co-Principal Investigator, Author, Audio Engineer

Most immersive microphone arrays assume reasonably sized point sources, especially concerning the placement of height microphones. However, the pipe organ is not often considered a reasonably sized point source. In turn, the established practices related to height microphone layer placement become unreliable in capturing a pipe organ performance for multichannel formats. The impact of height microphone layer position on perceived realism of a pipe organ recording is explored.

This publication (presented at the 157th Audio Engineering Society Convention) may be found here.

A Dolby Atmos binaural rendering of this recording is provided here, but a more in-depth comparison tool (uncompressed, including different binaural renderers and the ability to toggle between height microphone layer positions) may be found here.

Binaural Objects (2024)

Audio Engineer

Indicative of other mediums within immersive audio, binaural audio (especially when captured in binaural, as opposed to rendered) has as many drawbacks as it does utilities. Of these, perhaps the largest is limited playback options, as binaural audio is often restricted to headphones and nearphones.

Given this, what options exist for creating binaural content from the ground up? Of these options, do they prioritize binaural capture, or binaural rendering? Is there a large install-base/user-base for these options, or are they relegated to fringe use-cases with the occasional update?

To properly assess the state of the art in binaural-centric content creation, a flute performance of Arthur Honegger’s Danse de la Chèvre by Jessica Luo was captured with a Neumann KU-100 in a reverberant hall. Following this, a virtual soundscape was created with accompanying instruments in the box as a means to trial the capabilities of binaural-first software options.

The Carnival of the Animals Project (2022 - 2023)

Audio Engineer

In fall of 2022, I joined this grant-funded initiative as the audio engineer to 5 recordings of selected movements from Camille Saint-Saëns’ The Carnival of the Animals, for use within a 5 part educational video series distributed to elementary schools in rural communities across Indiana.

These performance recordings took place during October of 2022 in the Jacobs School of Music Auer Hall, with accompanying educational videos filmed and edited from 2022 - 2023.

Kian Ravaei, Feeling New Strength (2022)

Recording Engineer, Instructor

As a demonstration of methods to record large ensembles on a budget, Ravaei’s Feeling New Strength was captured with a total of four microphones: an XY stereo pair and two flank microphones. While this recording was done with a budget of around $1200, the principles discussed allowed for a budget less than half that.